Who’s On The Other Side Of Your Trade?

Who sets the price in 2026? A crisp map of today’s key market players—and how their impact shifts from calm to stress.

6 min read | Jan 23, 2026

Markets don’t move because “the market thinks.” They move because someone, somewhere has to trade—to rebalance, hedge, meet a mandate, manage risk, or implement a flow.

If you’re an allocator, CIO, or PM, that’s not just a neat line. It’s a practical edge.

Because a surprising number of “good” investment calls fail for a simple reason: they’re right on fundamentals, but wrong on who is setting the marginal price in that moment.

In 2026, that question matters more than it used to.

How we got to 2026: the three shifts that reshaped price-setting

The disappearing middle. For years, markets were stabilized by valuation-sensitive active managers with a 1–3 year horizon—adding risk into drawdowns and trimming into rallies. Over time, capital migrated to the extremes: toward low-cost passive on one side, and toward high-fee alternatives and systematic strategies on the other. The result is fewer natural buyers stepping in “between” earnings cycles. When a mechanical wave hits—hedging, de-grossing, index flow—price can travel further before it meets genuine valuation support.

Constraints replaced discretion at the margin. Even when investors are discretionary, risk systems, liquidity caps, factor neutrality, and drawdown limits increasingly dictate behavior when volatility rises. This is where multi-manager platforms are central to the 2026 regime: they are built to harvest idiosyncratic alpha while neutralizing beta, but their tight risk budgets can synchronize behavior across pods. In calm markets, that looks like disciplined market-neutral trading. In stress, it can become sudden de-grossing that feels directional.

Systematic macro became a regime engine. CTAs and vol-managed allocation have become a powerful medium-horizon layer. In calm regimes, they reinforce trends. In stress regimes, they can accelerate cascades when vol rises or signals flip. They don’t need to “believe” anything about intrinsic value to move markets—only a model and a trigger.

The 2026 barbell market: why opponent modeling matters again

Put those shifts together and you get a market that feels increasingly barbelled across time horizons:

- At one end: ultra-fast participants shaping microstructure—market makers, HFT liquidity, derivatives hedgers.

- At the other: ultra-long capital—strategic allocators, passive vehicles, sovereigns, corporate buybacks.

- In the middle: professional relative-value and discretionary investors—equity L/S, event-driven, quant market-neutral, and multi-manager pods—operating under tighter constraints and faster risk limits.

This doesn’t mean fundamentals don’t matter. It means fundamentals can be temporarily overruledby flows and constraints—sometimes for longer than most investors expect.

So the key question becomes: who are you actually trading against when you express your view?

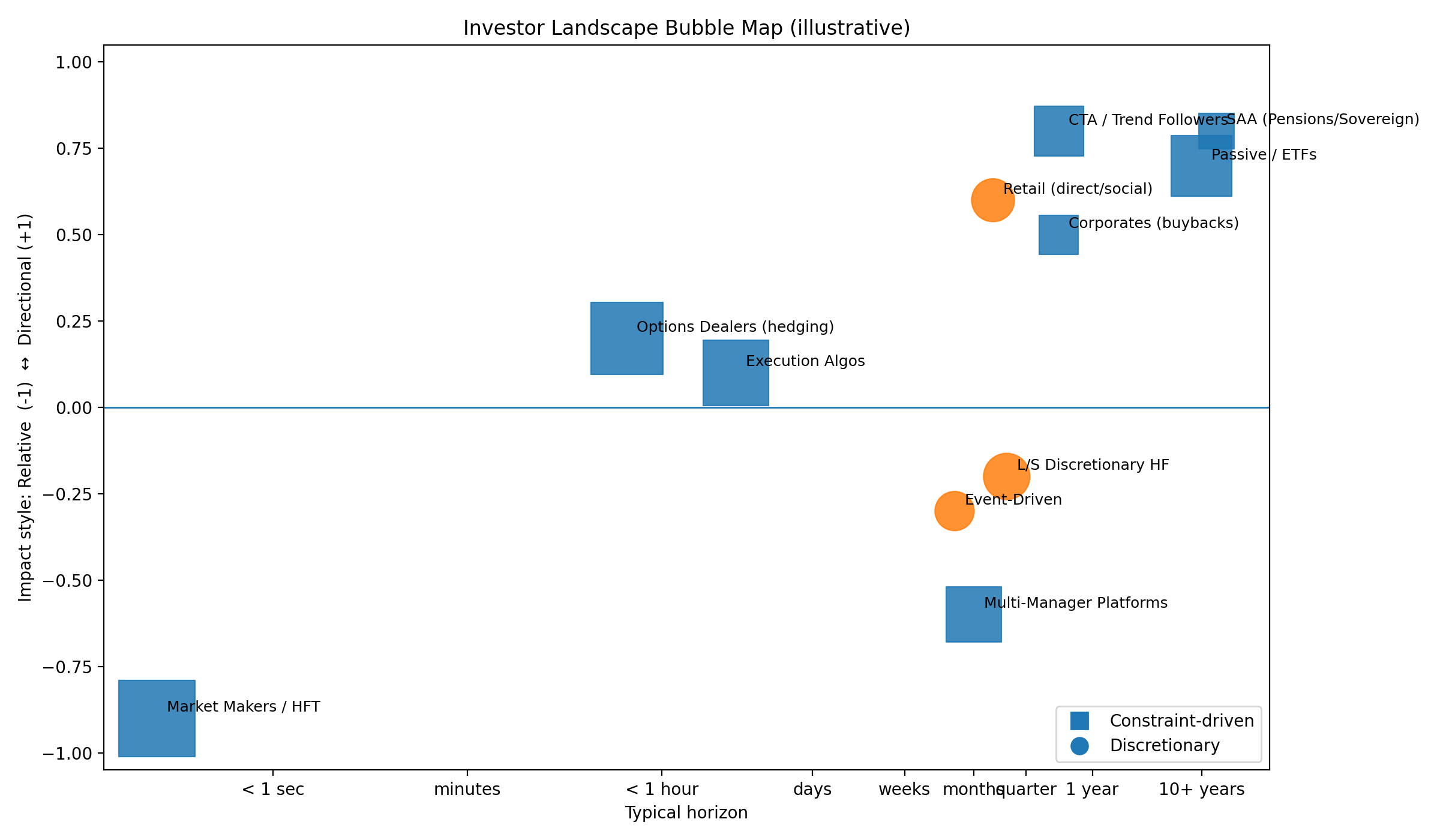

A better classification: not style labels, but price impact mechanics

Most investor taxonomies start with labels—value, growth, hedge funds, passive. Useful, but incomplete. If your goal is to understand who sets the marginal price, two simpler questions are often more powerful:

First: is the impact mostly relative or directional?

Relative players push spreads—winners versus losers, sector-neutral longs versus shorts, factor baskets. Directional players push beta—net buying or selling of the market or broad baskets.

Second: is the behavior discretionary or constraint-driven?

Discretionary means someone is choosing risk because they see mispricing. Constraint-driven means risk changes because rules force it: hedging, rebalancing, vol targets, risk limits, drawdowns, mandate mechanics.

That second axis is the part most investors underweight. In 2026, a growing share of price action—especially during stress—is not a debate about valuation. It’s a chain reaction of constraints. And that’s exactly what the next charts make visible.

The Investor Landscape Map

This chart lays out the main market participants along two simple axes: time horizon and the type of impact they tend to have—relative (spread-setting) versus directional (beta-setting). What stands out is the “barbell”: very fast actors on the left (liquidity provision and hedging) and very slow actors on the right (strategic ownership and policy portfolios), with the professional “middle” in between.

The key point is not the labels. It’s the mechanics. In calm markets, the middle can look like a collection of independent relative-value players. In stress, it often behaves as a tightly coupled system because constraints (risk limits, deleveraging, liquidity) synchronize actions. That’s why markets can overshoot fundamentals: price is sometimes set by who must trade, not who is most right.

Transmission Matrix - Calm Regime

The calm matrix answers a dynamic question: when pressure appears in one part of the ecosystem, how strongly does it force other participants to reprice or trade? In calm regimes, the system is looser. Shocks are more likely to be absorbed locally, and feedback loops are weaker. That’s why markets often feel “two-way” and mean-reverting when volatility is low.

For CIOs and allocators, this is the environment where diversification looks strongest. Many strategies appear uncorrelated because the transmission channels between them are weak. For PMs, it’s the regime where idiosyncratic stock selection and spread trades tend to behave as expected—because flow spillovers are limited.

Transmission Matrix - Stress Regime

The stress matrix shows the same ecosystem under pressure. This is where the market starts to behave less like a collection of opinions and more like a system of constraints. Transmission channels strengthen. Forced flows propagate. Strategies that looked different in calm suddenly move together because they share similar exit doors.

This is also where certain players become “price setters” by necessity. Multi-manager platforms can de-gross quickly. CTAs can reinforce moves. Passive flows can become indiscriminate. Dealer hedging can amplify intraday swings. The important shift is simple: the marginal trade is increasingly driven by mandates and risk rules, not discretionary valuation.

The practical question: who is your counterparty?

If you’re a CIO / allocator: your opponent is hidden concentration. You’re underwriting liquidity behavior under stress, not just manager skill. Which sleeves share the same exit doors? Which ones become forced sellers together? Which ones structurally provide liquidity versus consume it?

If you’re a value investor (1–3 years): your opponent is forced selling. Trend-following flow, de-grossing in multi-manager books, and passive outflows can push price well below fundamentals. Your edge is patience and underwriting—but timing often comes from recognizing when forced sellers are exhausted.

If you’re a swing trader (weeks to months): your opponent is positioning around catalysts. Around earnings, price is often set by equity L/S repositioning, multi-manager netting, and hedging flows. If a company beats and the stock drops, it can be positioning—not story.

If you’re a macro PM (6–12 months): your opponent is the flow regime. Passive risk-on/risk-off flows, CTA trend reinforcement, and vol-managed deleveraging can dominate tape direction for long stretches. Your advantage is separating information from flow.

Stop asking “what does the market think?”

Start asking:

- Who has to trade?

- Which constraints are binding?

- Which transmission channels intensify in stress?

- Where does my strategy sit on the landscape map?

In 2026, that’s often the difference between being right, and getting paid.

Resonanz insights in your inbox...

Get the research behind strategies most professional allocators trust, but almost no-one explains.