The Total Cost of Alternatives: A Fee & Terms Budgeting Framework for Absolute-Return Allocations

Framework for comparing hedge funds, UCITS, and QIS on all-in fees, liquidity, and hidden costs, helping allocators maximize net absolute returns.

12 min read | Aug 20, 2025

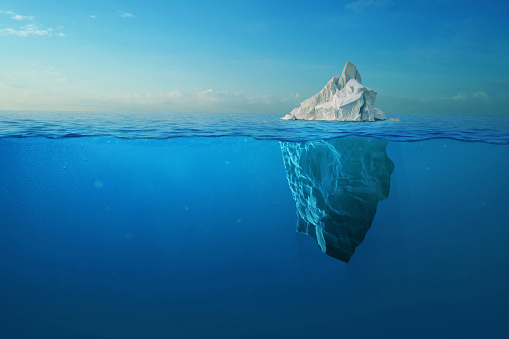

Institutional investors and family office CIOs know that not all “absolute-return” vehicles are created equal. Hedge funds, UCITS liquid alternatives, and bank-provided QIS products can all deliver alternative strategies – but each comes with its own blend of fees, expenses, and liquidity terms. Making apples-to-apples comparisons is notoriously challenging. A hedge fund might deliver stellar gross returns but layer on hefty fees and lock-ups, while a leaner UCITS or QIS index may offer lower fees and daily liquidity at the cost of strategy constraints.

A Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) mindset expands the view of costs to include not just headline fees but all frictions and terms risks that erode net returns.

Defining Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) in Alternative Investments

When we hear “hedge fund fees,” the first thing that comes to mind is the classic “2 and 20” fee structure (e.g. 2% management fee and 20% performance fee). But limiting our analysis to just the obvious fees would grossly underestimate the true cost of an alternatives allocation. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for alternative investments encompasses every expense, drag, and friction that eats into your returns. Let’s break down the components of TCO for absolute-return strategies:

TCO aggregates every drag on performance:

-

Management fees – 1–2% for hedge funds, often less for UCITS, fixed index fees for QIS.

-

Performance fees – 15–20% common for hedge funds; understand hurdles, resets, high-water marks.

-

Pass-throughs – research, data, admin, travel; more common in platform models.

-

Borrow & financing costs – stock borrow, repo, collateral carry.

-

Execution slippage & spreads – especially in less-liquid strategies.

-

Derivative carry – swaps, futures roll.

-

Total Return Swaps (TRS): QIS strategies are often delivered via swaps, with the bank charging a spread or fee embedded in the swap rate.

-

Futures and Roll Costs: If a strategy uses futures for exposure, as in many CTA and risk premia approaches, rolling in contango markets can steadily erode returns through roll costs.

-

Structured Notes and Wrappers: An absolute-return strategy delivered via a bank note, UCITS capital-guaranteed structure, or insurance-linked wrapper may embed upfront or ongoing structuring fees, so always identify the extra costs built into the delivery format.

-

-

Structuring / OCF – platform, SPV, or fund-of-fund costs.

-

Tax drag – WHT, UBTI, PFIC, domicile effects.

In short, TCO = Management Fees + Performance Fees + Fund Expenses + Trading Frictions + Financing & Leverage Costs + Structural Fees + Tax Drags (+ any miscellaneous pass-throughs). It’s the sum total of what you pay and what you give up in performance bleed. This comprehensive view is crucial for comparing alternatives on a level playing field. For example, a hedge fund charging “2 and 20” might also generate higher trading costs (if it’s very active) and pass-through expenses, whereas a QIS index charging a 1% index fee might have low turnover and no other layers – the headline fee gap may understate the true difference.

Budgeting for “Terms Risk”: Illiquidity as a Cost Constraint

Fees are only half the story – the terms of an investment (lock-ups, liquidity, redemption provisions) carry their own kind of “cost.” Unlike explicit fees, illiquidity and restrictive terms don’t show up on an invoice, but they impose economic costs and risks that must be budgeted. We call this “Terms Risk”: the risk or cost you bear from an investment’s liquidity terms. How can we quantify and manage this? Treat liquidity as a scarce resource – one that you budget and allocate deliberately, just like fees.

Common liquidity terms and their impact:

-

Lock-ups – initial hard or soft lock.

-

Notice periods – 30–90+ days.

-

Gates / side-pockets – suspension triggers.

-

NAV frequency – daily for UCITS, monthly/quarterly for many hedge funds.

-

Settlement lags – T+30 or more.

Quantifying Terms Risk: Unlike fees, we can’t add up terms costs in dollars easily, but we can set limits and guidelines. For example:

-

Assign an “illiquidity score” to each investment (e.g. 1 for daily, 2 for weekly, 5 for quarterly with 90-day notice, 8 for annual or longer). Then set a limit that the weighted-average score of your alternative portfolio should not exceed a certain level. This way, if you include a very illiquid fund, you counterbalance with more liquid ones.

-

In investment committee discussions, explicitly ask: “What is the liquidity cost here, and are we being paid for it?” If a fund with a 2-year lock is expected to return, say, 8% net, would we be better off in a liquid alt returning 6% net? If that 2% return pickup is mostly because the fund is locking our money (and others can’t arbitrage it away), maybe it’s justified – but if not, think twice.

-

Consider worst-case scenarios: e.g. “If this fund gates, how badly could that impact our portfolio or operations?” If the answer is unacceptable, that in itself is a cost (potentially forcing you to have higher cash buffers elsewhere).

Apples-to-Apples Fee Comparison: Converting Fees and Terms into Basis Points

With a clear view of all fee components and a handle on terms risk, the next step is to standardize your comparisons. Different vehicles quote fees in different ways, and performance fees introduce nonlinear outcomes. An effective approach is to translate everything into an annualized cost in basis points on the amount of capital deployed, and then adjust for terms. Here’s how:

1. Standardize Management Fee Basis: Some private market funds charge fees on committed capital, so if capital isn’t fully deployed, convert this to an invested-capital equivalent (e.g., 1% on 50% deployed is effectively 2%). Hedge funds usually charge on NAV, so ensure all vehicles are compared on an apples-to-apples invested-capital basis.

2. Normalize Performance Fees: Estimate performance fees under realistic scenarios, adjusting for hurdles, volatility, and path dependency. For volatile or multi-strategy funds, the effective rate can exceed the headline—model multi-year outcomes and, if needed, add an “asymmetry premium” to ensure comfort with potential fee drag.

3. Build a Comparability Grid: It can help to create a simple table for each prospective investment, listing:

- Management Fee (bps) – on whichever base (note if on committed).

-

Performance Fee – include hurdle? HWM? (Maybe note “20% (HWM, no hurdle)” for one, vs “15% (annual hurdle 3%)” for another).

-

Expected Perf Fee (bps) – your estimate of what that might equate to annually (e.g. “~160 bps assuming 8% gross”).

-

Fund Expenses (bps) – include any pass-through or additional fees.

-

Trading/Financing Costs (bps) – this one is qualitative, but you could say high, medium, low. Alternatively, estimate if known (e.g. “strategy uses 50% leverage, ~50 bps interest cost”).

-

Liquidity Terms – lock-up in days, notice period, redemption frequency.

-

“Liquidity Cost” – another column where you score or assign bps for illiquidity. Perhaps “~100 bps for 2-yr lock” as per the study, or “minimal” for daily liquid.

-

Total Equivalent Cost – sum of all the bps (explicit fees + estimated implicit + liquidity cost).

| Vehicle | Mgmt Fee | Perf Fee (hurdle?) | Est. Perf Fee (bps) | Other Exp (bps) | Liquidity | Illiquidity Cost | Est. TCO (bps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedge Fund (Offshore) | 2% on NAV | 20% (HWM, no hurdle) | ~160 bps (8% gross) | ~20 bps fund exp | Qtrly, 1-yr lock, 25% gate | ~100 bps | 280 + perf ≈ 460 |

| UCITS Alt Fund | 1.5% on NAV | 15% (annual 0% hurdle) | ~90 bps (6% gross) | ~50 bps OCF | Daily liquidity | ~0 (daily) | 200 + perf ≈ 290 |

| QIS Index Swap | 0.75% index | 0% (n/a) | 0 bps | ~25 bps (swap) | Daily (note: bank swap) | ~0 (daily*) | 100 (all-in) |

Source: Resonanz Capital

Finally, incorporate path-dependent considerations: If a fund has a high-water mark, recognize the option value that accrues to you (fee credit after losses). Just be aware that if you leave the fund or it winds down, that credit is lost – effectively a donation of past fees. So in comparing a single-strategy hedge fund vs a multi-strat platform, note that multi-strat (with multiple teams inside one fund) might actually be more efficient fee-wise than many single funds where you might drop some after losses (losing fee credits). These nuances can be complex, but the TCO framework prompts you to think through them.

Fee-for-Skill Calibration: How Much Alpha Justifies the Fees (and Locks)?

One of the most important questions an allocator can ask is: “For this strategy, what net return (alpha) do we expect, and is it worth the total fees and terms?” In other words, calibrate the fees you are willing to pay to the skill and value-add of the manager. This is the essence of fee-for-skill calibration. Rather than universally insisting on low fees, the idea is to pay up when it’s truly worth it – and avoid overpaying for strategies that don’t need superstar talent.

Pay up for:

-

Scarce alpha in inefficient markets.

-

Demonstrated persistence across cycles.

-

Structural capacity constraints that support pricing power.

Push back when:

-

Alpha is cyclical, beta-dependent, or crowded.

-

Liquidity terms are misaligned with asset liquidity.

A concrete example: Equity Market-Neutral Fund A and Equity Statistical Arbitrage Index B might both aim for 5% gross above cash. Fund A charges 2/20, no hurdle; Index B costs 1% with no perf fee. If they both indeed generate 5%, Fund A investor could net maybe ~2%, whereas Index B nets ~4%. Unless you believe Fund A can actually generate much more than 5% (through skill) or provides some hard-to-replicate benefit, Fund A’s fees are not calibrated to its likely alpha – you’d lean toward Index B or negotiate Fund A down (maybe ask for a 5% hurdle and lower perf fee). On the other hand, Distressed Debt Fund C charges 1.5% and 15%, but targets 12% gross by investing in off-the-run bankruptcies – here paying those fees to net ~8-9% might be acceptable, because no cheap replication exists and the managers have a real edge in that niche.

Crowding & Capacity: The Hidden Cost of Diminishing Returns

Beyond explicit fees and terms, crowding and capacity constraints act as implicit costs that reduce returns when too much capital chases the same trades. Crowding occurs when many managers hold similar positions or factor exposures, eroding alpha and amplifying drawdowns in unwind scenarios; capacity is the point where a strategy’s size starts to harm its own performance.

Monitor both with factor crowding analysis, holdings overlap checks, and honest discussions with managers about capacity. Include a crowding or active-share KPI in your monitoring, and diversify across genuinely different strategies to avoid paying for the same crowded alpha twice. If crowding rises or capacity is breached, expect lower net returns—sometimes by more than you save in fee negotiations.

The TCO Toolkit: Scorecard, IC Decision Rules, and KPI Monitoring

We’ve covered a lot of ground – now how do we operationalize this TCO and terms risk framework? Here are some practical tools and steps to embed these concepts into your investment process:

1. TCO & Terms Scorecard

Use a one-page template for every alternative allocation. Include: strategy/vehicle type, full fee breakdown, liquidity terms, estimated net performance (range for good/bad cases), a combined cost score, and qualitative notes (capacity, crowding). This ensures decisions are made with a complete cost picture, not just return projections.

2. IC Decision Guidelines

Set principles to keep discipline, e.g.: avoid mgmt >2% or perf >20% without strong cause; limit lock-ups >1 year unless returns justify; prefer investor-friendly liquidity; target an average fee load; require hurdles where possible; and re-evaluate or negotiate if net returns lag peers.

3. Ongoing KPIs

Track actual fees paid in bps, net performance vs relevant benchmarks, portfolio liquidity profile, look-through leverage, crowding indicators, manager AUM growth, and quality of client servicing. Use these in a quarterly dashboard for the IC to spot issues early.

4. Continual Reassessment

Leverage your TCO analysis when negotiating fees or terms—many managers will adjust for committed capital. Regularly reassess alignment between costs, terms, and delivered value. The goal is to make fees and liquidity central to allocation decisions, not an afterthought.

Conclusion

In alternatives, focusing only on gross returns risks ignoring the drag of fees and the limits of illiquidity. A TCO mindset—budgeting fees and terms alongside risk and return—helps ensure you pay for true value and avoid avoidable costs. By identifying all cost components, quantifying terms risk, standardizing comparisons, and enforcing discipline with scorecards and KPIs, you can materially improve outcomes. Two investors in similar strategies can have very different results depending on negotiation and liquidity; every basis point saved or gained in flexibility compounds over time. Equip your IC with this framework, ask “what are we truly paying, and why,” and you’ll keep more of the alpha you seek—optimizing for net, risk-adjusted, real-world results.

Resonanz insights in your inbox...

Get the research behind strategies most professional allocators trust, but almost no-one explains.