Co-investments In The Context of Hedge Funds

Hedge funds use co-investments to pursue unique opportunities, offering investors higher returns, common goals, and reduced fees.

4 min read | Oct 19, 2022

Traditionally, co-investments were part of the playbook of the PE industry (but also real estate, infrastructure and energy partnerships) for many years. Over time, they have been gradually adopted by the hedge fund industry (and other liquid alternatives), pioneered by activist managers. Today, co-investments have evolved into an important tool to increase the total return of portfolios, while limited correlation to traditional asset classes and core hedge fund strategies. They have also proven to be an effective tool to respond more rapidly to dislocations in markets.

What Is Behind The Growth In Hedge Fund Co-Investments Opportunities?

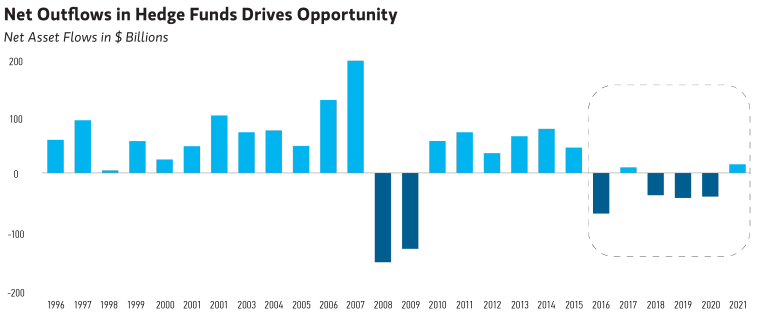

Prior to the GFC, the hedge fund industry experienced strong inflows, while hedge funds enjoyed relative freedom to pursue niche opportunities and put less liquid investments into side pockets. However, recent years have been marked by more limited industry inflows, and investors have been more restrictive on permissible investments within the flagship commingled vehicles, particularly less liquid situations. As a result, hedge funds have had less discretionary capital available to deploy.

Hedge funds naturally turned to co-investments as a new form of capital that would allow them to pursue discrete, high-conviction opportunities that do not necessarily fit the mandates of their main funds in terms of liquidity, concentration or asset class guidelines. Investors, on the other hand, saw co-investments as complementary block to their hedge fund allocations offering direct access to differentiated sources of return, bespoke risk/return profile as well as attractive fees, transparency and control rights over the underlying assets.

As a result, hedge fund co-investments have become increasingly popular and a recurring theme within hedge fund investor surveys in recent years, as a growing number of allocators are investing alongside hedge funds:

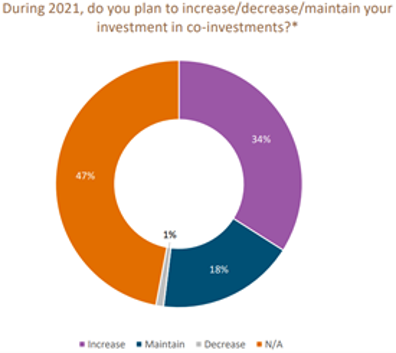

In the meantime, a growing portion of such allocators are planning to increase exposure to the space, as shown in J.P.Morgan’s 2021 investor survey where one-third of investors planned to increase exposure to co-investments in 2021:

What Co-Investments Are Being Offered By Hedge Funds?

In contrast with PE co-investments, which are homogenous in that they involve control private equity positions with PE-like holding periods, hedge fund co-investments involve a wide spectrum of diverse asset classes with time horizons falling between those of hedge funds and those of private equity. Despite their diversity, they tend to present the following characteristics:

- Scalability: warranting extra time and effort to underwrite

- Illiquidity: stemming from the required position size or lack of pricing, hence the need for longer lock-ups

- Time-sensitivity: requiring quick decision-making

Furthermore, given these common characteristics, the strategies that are likeliest to pitch co-investment ideas to investors include activists, equity long/short and credit:

- Stressed/distressed corporate credit (e.g. Lehman claims, Icelandic debt, bank loan liquidations)

- Structured credit (e.g. CLO equity, CDO of trust preferred securities)

- Sovereign and/or municipal debt (e.g. Argentinian debt, Nigerian or Egyptian T-bills, Puerto Rico or Buenos Aires bonds)

- Event-driven equity

- Late-stage private equity (e.g. pre-IPO)

What Benefits For The Investors And The Managers?

The table below summarizes the main benefits for both the investors and the hedge fund managers that co-investment structures can provide:

How Are Co-Investment Vehicles Structured?

The structures that managers are using tend to be idiosyncratic rather than standardized. However, certain patterns emerge for various manager types with respect to the structural permutations used for co-investment vehicles.

In fact, activist managers as well as credit-oriented managers presenting high conviction ideas in co-investment structures would tend to use truncated private equity-like structures (i.e. draw-down structures), i.e. with features that are differ from the private equity world such as a shorter term and the possibility of offering bespoke redemption features.

Single-deal co-investments are another form of structure which exhibits features that are more hedge fund-like. These are most often used by managers with shorter-term, trading-oriented strategies. Such SPVs are run as separate hedge funds (both co-mingled funds and single investor funds) and therefore have their own prime brokerage agreements and investment management agreements between the manager and the limited partner(s). Finally, single-deal vehicles tend to lack the benefits of netting that multi-investment vehicles provide, and offer no recourse to the manager’s main fund. Consequently, single deal co-investments are more appropriate for investors with more tolerance for risk and volatility.

The table below summarizes key representative terms for these three models of co-investments:

Resonanz insights in your inbox...

Get the research behind strategies most professional allocators trust, but almost no-one explains.