The Premium Income Mistake: Why "Equity Premium Income" Isn't the Income You Think It Is

A field guide for RIAs, family offices, and institutional allocators who need to explain what their clients actually bought

10 min read | Feb 17, 2026

A family office CIO shared a real-life story with me recently. His principal—a retired tech executive—was furious. The "high-income equity strategy" they'd allocated $3M to in early 2024 had just lagged the S&P 500 by 22 percentage points during one of the strongest six-month rallies in years.

"But we're getting 8% yield," the CIO protested. "The distributions hit every month like clockwork."

"Right," I said. "And what did you give up to get that 8%?"

Long pause.

"I thought we were just harvesting dividends more efficiently."

This conversation happens every cycle. The structure changes—covered calls, equity-linked notes, systematic overwrite, "premium income," whatever the current wrapper is—but the misunderstanding is identical: advisors and allocators mistake option premium for safe carry, and treat short convexity like an income asset.

That's not a moral failing. It's a product design feature. These strategies look like yield because the distribution is visible and measurable. The trade-off—capped upside, embedded short volatility, regime-dependent income—is invisible until it hurts.

If you're an RIA explaining to clients why their "equity income" fund didn't participate in the rally, a family office allocator stress-testing a JEPI allocation, or an institutional investment committee member trying to figure out where premium income actually fits in the portfolio, this is for you.

What You're Actually Buying (and Selling)

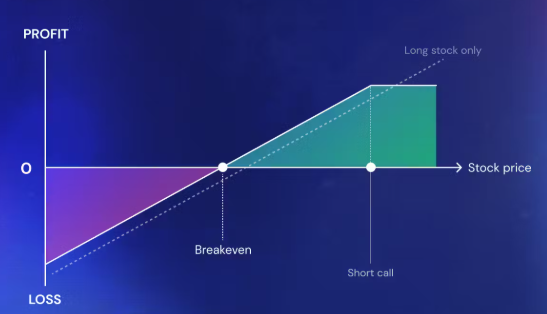

Covered call and "equity premium income" products are not dividend strategies. You are not "harvesting income." You are selling future upside in exchange for cash today, and you are embedding a short-volatility profile into what looks like an equity allocation.

That can be a sensible choice in the right portfolio role. It becomes a problem when:

- It's treated as core equity (it will structurally lag in sustained rallies)

- The yield is interpreted as "safe carry" (it's not—it's regime-dependent and tied to implied volatility)

- Clients expect bond-like stability with equity-like returns (the payoff is neither)

Most disappointment traces back to three mechanical realities that get buried in marketing materials:

- Upside is capped by the call you sold—gains above the strike go to the call buyer, not you

- Downside is not capped—the premium you collected is a small buffer, not protection; you still own full equity drawdown risk

- Income is regime-dependent—when implied volatility falls (VIX compression), option premium falls with it, and your distributions shrink

What these products actually do

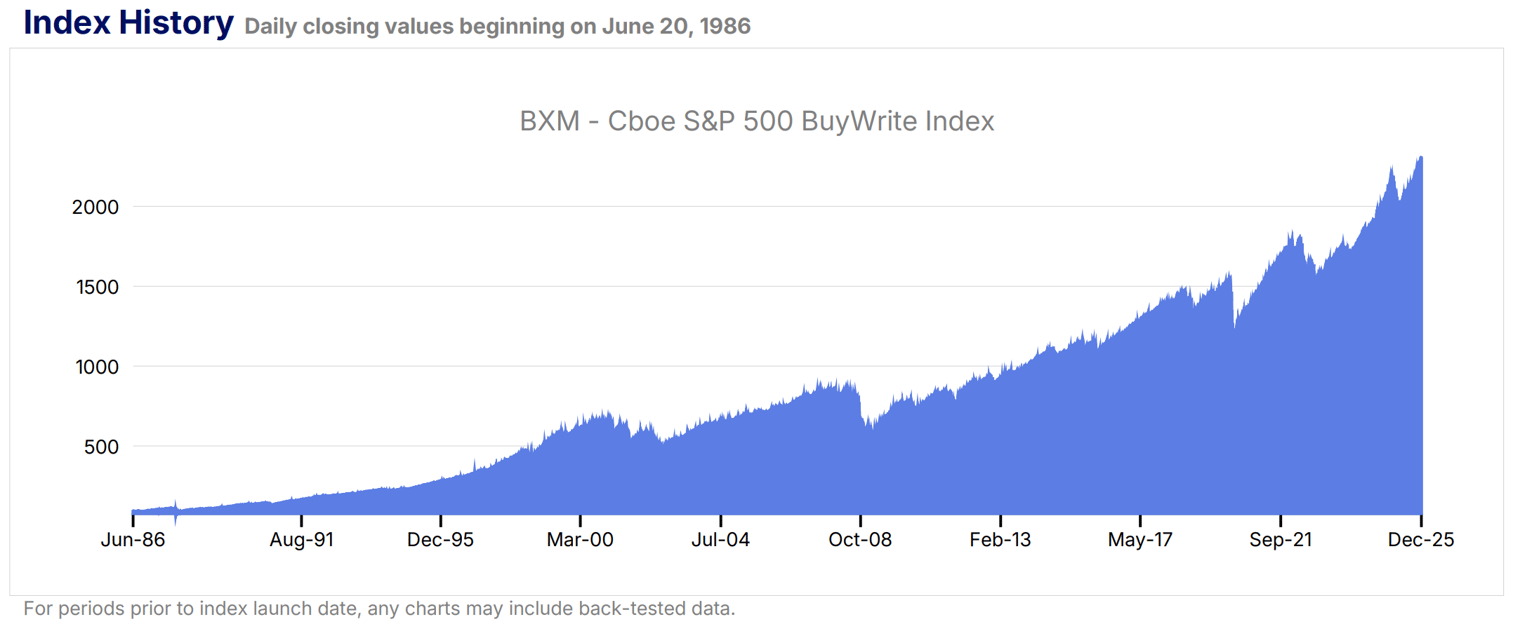

At the cleanest end, a classic buywrite does exactly what you’d do manually: hold the equity exposure and sell index calls against it.

A widely used benchmark is the Cboe S&P 500 BuyWrite Index (BXM):

-

long S&P 500 exposure

-

Systematically sell one-month, at-the-money S&P 500 calls

-

Rolling monthly

Source: Cboe, as of December 2025

Variants shift the trade-off:

- OTM overwriting (e.g., “30-delta” calls) sacrifices less upside, but generates less premium. Cboe’s methodology explicitly distinguishes BXM (ATM) from BXMD (30-delta).

- Partial overwrite writes calls on only part of the equity exposure (less yield, less cap).

- Dynamic overwrite adjusts strike/coverage based on volatility or trend (more model risk; potentially better behavior in extremes).

Then you have modern "equity premium income" wrappers. Many large funds aren't literally writing covered calls on each equity holding. They hold an equity portfolio and use derivatives overlays to monetize option premium.

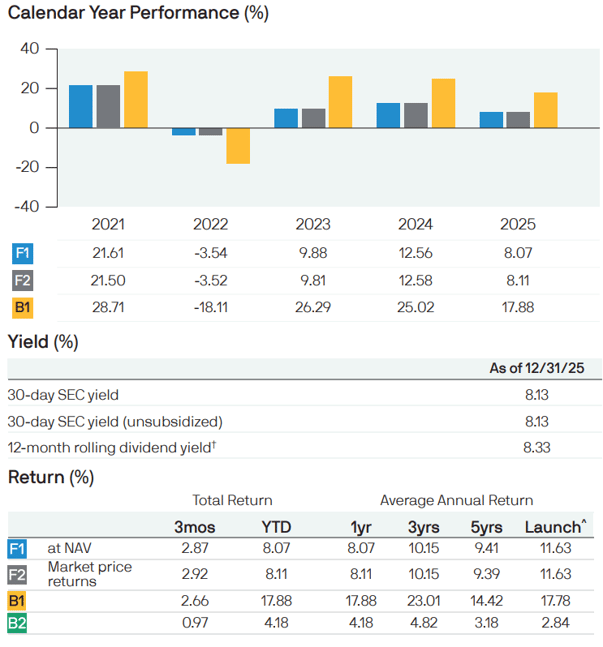

Example: JPMorgan Equity Premium Income ETF (JEPI) describes generating income via "selling options" alongside a low-volatility equity portfolio. It reports significant fund size and a meaningful SEC yield—but this is a derivatives income product in practice, not a dividend fund.

Source: JPMorgan AM; as of December 2025

The core trade you’re making: you’re selling convexity

A covered call is short convexity. In plain language:

- If equities grind higher slowly: You can look great. Premium accrues, volatility often bleeds, and the call may expire with manageable opportunity cost.

- If equities rip higher: You lag because gains above the strike go to the call buyer.

- If equities gap down: The premium is small relative to the drawdown. You still own the equity risk; you just collected a small upfront rebate.

This payoff shape isn't "good" or "bad"—it's a profile. The underwriting question is whether that profile belongs in the sleeve you're funding it from.

| Structure | How it’s implemented | What you give up | What you get | Best portfolio use | Key risks to flag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATM full overwrite (BXM-like) | Long equity + sell 1M ATM index calls | Most upside in rallies | Highest premium, lower vol | Equity risk reducer / distribution smoother | Persistent rally underperformance; short convexity |

| OTM / 30-delta overwrite (BXMD-like) | Long equity + sell OTM calls (delta target) | Less upside (but still capped) | Moderate premium | “Core-ish” equity with mild overwrite | Still short convexity; income drops in low vol |

| Partial overwrite | Sell calls on only part of exposure | Less upside sacrificed | Lower premium | Fine-tuning risk budget | Design complexity; drift |

| Active “premium income” + ELNs (JEPI-like) | Equity portfolio + option exposure via ELNs/overlay | Depends on overlay design | Premium + equity selection | Outcome-oriented sleeve (benchmark carefully) | Counterparty/liquidity/valuation risk (if ELNs), opacity |

Why the headline yield is seductive—and often misunderstood

Three points I make in IC meetings when these strategies show up as “income alternatives”:

- Yield is not return.

A high distribution can coincide with mediocre total return if the equity sleeve drifts down or upside is repeatedly clipped. Your client sees "8% income" but misses that their account value is flat or down. - Income is not stable.

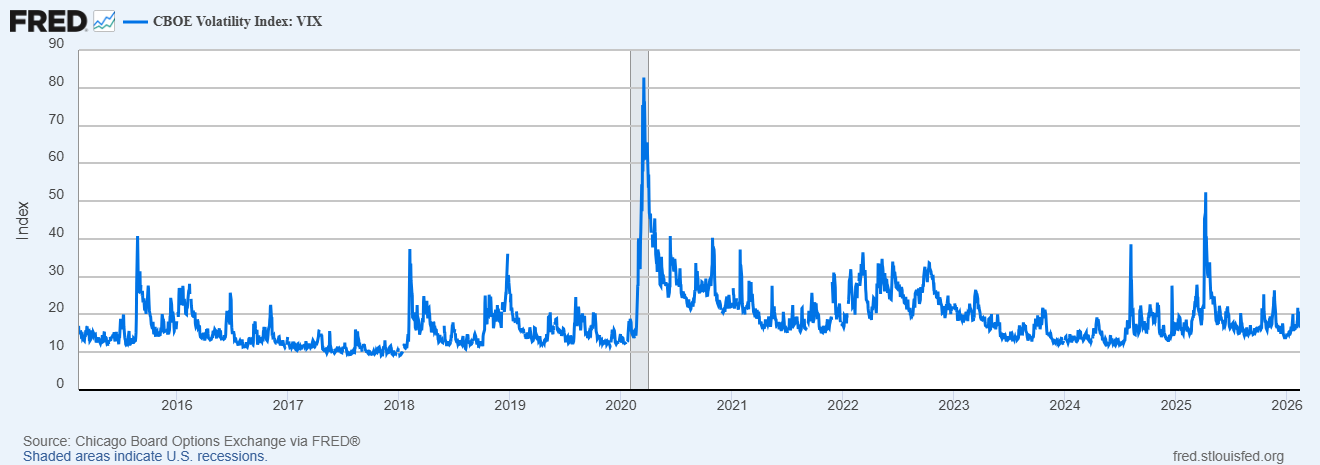

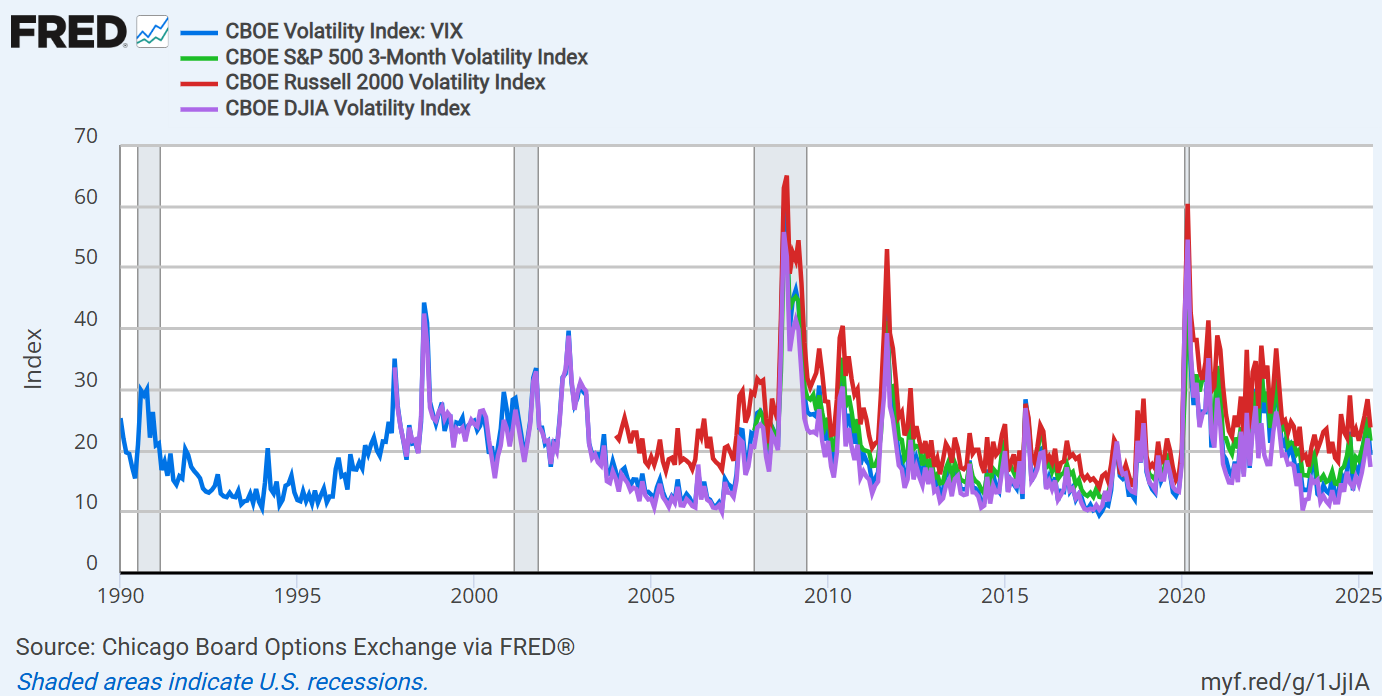

Option premium is strongly linked to implied volatility. When volatility normalizes lower, distributions compress.

VIX as a proxy: When VIX sits at 12-14 (calm markets), there's less option premium to harvest. When VIX spikes to 25-35 (stressed markets), premium looks rich—but that's often when equity conditions are terrible and gap risk is highest.

Source: Cboe via FRED - The product label hides the risk budget.

Many investors treat "premium income" as if it belongs near credit or structured income. It doesn't. It's equity beta plus an option-selling overlay. A fund like JEPI explicitly positions itself as equity exposure plus option premium generation. That's not a bond substitute—it's an equity allocation with a specific payoff modification.

What can go wrong (and what to watch)

1) Sharp rallies: you sell the upside you wanted

Covered call strategies structurally underperform in strong, trending bull markets because your upside above the strike is gone. The more “income” you target (ATM, higher overwrite), the more upside you forfeit.

What to watch

- Overwrite level (100% vs partial)

- Moneyness (ATM vs OTM/delta target)

- Roll frequency (monthly vs weekly)

- Whether the strategy is systematic or discretionary (governance matters)

2) Crashy markets: premium is a thin buffer, not protection

In a fast drawdown, the option premium you collected is quickly overwhelmed. You still participate in most of the equity downside. The strategy can reduce volatility over time, but it is not a hedge.

What to watch

- Downside convexity: is there any put budget or is it pure overwrite?

- Drawdown policy: are there rules to reduce overwrite after a shock (often too late), or to maintain it (can stabilize income but locks in low recovery participation)?

3) Volatility regime shifts: the “income” disappears when you need it most

Option premium is rich when implied vol is high. That’s when distribution optics look best. But high vol also tends to coincide with stressful equity conditions and higher gap risk. When vol later compresses, premium shrinks—often while investors have come to rely on the distribution.

What to watch

- A stated mechanism linking distributions to option premium (not smoothing language)

- Your portfolio’s reliance on that cash flow (don’t fund fixed spending with variable premium unless you have buffers)

4) Implementation risk: “covered call” can be implemented three different ways

Index buywrite is simple. Many funds are not. Some use index options directly; some use structured notes; some overwrite subsets of holdings; some write on benchmarks while holding factor-tilted equities.

JEPI, for instance, discloses Equity-Linked Note (ELN) risks (liquidity, valuation, counterparty) alongside the equity risk. Those are real underwriting items.

What to watch

- Instrument: listed options vs OTC note

- Counterparty exposure and collateralization (if OTC)

- Liquidity of the overlay during stress

- Tax character of distributions (portfolio-level consequence, especially for taxable clients)

A decision tree: “Should this be in your portfolio?”

Use this as a quick pre-filter before you get lost in yield charts.

Step 1: What problem are you solving?

- Need equity-like return with smoother ride → consider partial overwrite / OTM overwrite, sized modestly.

- Need stable contractual income → this is the wrong tool. Use bonds/structured credit/annuities, not short-vol equity overlays.

Step 2: Can you tolerate underperforming in melt-ups?

- If “no” (you benchmark to equity strongly) → do not use ATM/full overwrite as core equity.

- If “yes” (you value drawdown/vol control more than upside capture) → proceed.

Step 3: Where does it sit in the risk budget?

- If you’re funding it from equity → coherent.

- If you’re funding it from defensive/income → you’re smuggling in equity beta and short convexity.

Step 4: Which implementation matches your intent?

- Want transparency and mechanical rules → index-like listed option overwrite (benchmarkable to BXM/BXMD).

- Want manager discretion (stock selection, overwrite timing) → accept manager risk and require process evidence.

Step 5: Size it like an overlay, not a replacement

- Typical outcome: treat as a satellite sleeve or a distribution smoother, not a core equity substitute.

Myths vs reality (FAQ)

Myth: “Covered calls reduce downside risk.”

Reality: Premium provides a modest buffer, but you still own equity drawdown risk. It’s not a hedge; it’s a rebate.

Myth: “The yield is ‘income’ like coupons.”

Reality: It’s primarily option premium plus whatever dividends the equity sleeve generates. That cash flow varies with volatility and market path. VIX is a simple public indicator of the premium regime.

Myth: “I’m getting paid to wait.”

Reality: You’re getting paid to give away a slice of upside and to carry short-vol exposure. That’s fine—if you intended to sell that.

Myth: “All covered call ETFs are basically the same.”

Reality: Overwrite %, strike selection, roll timing, and instrument choice (listed vs ELN) produce very different outcomes. Cboe’s own buywrite family demonstrates that ATM vs 30-delta is a materially different exposure.

Myth: “This is safer than equities because volatility is lower.”

Reality: Lower realized volatility does not mean lower tail risk. Short convexity can look stable until it doesn’t.

Myth: “If it’s an ETF, the implementation must be straightforward.”

Reality: Read the risk section. JEPI explicitly highlights ELN liquidity, valuation, and counterparty risk. That is not the same as “sell a call on SPX.”

Conclusion: allocator takeaways

If you take nothing else from this piece, remember these five points:

- Treat covered call / equity premium income as equity + option-selling overlay, not as a bond substitute.

- Underwrite the payoff shape: capped upside, largely uncapped downside, and regime-dependent income (volatility-driven).

- Know your benchmark: compare to mechanical references like BXM (ATM overwrite) or BXMD (30-delta overwrite) so you can separate “strategy beta” from manager value-add.

- Demand clarity on implementation: listed options vs ELNs/OTC overlays materially change liquidity and counterparty risk.

- Size it appropriately: if you can’t tolerate lagging in sharp rallies, don’t hold an ATM/full overwrite sleeve as “core equity.”

What Happens Next?

You now understand the mechanics. You know what can go wrong. The harder question is: does this belong in your portfolio, and if so, where?

If you're still not sure—or if you need to explain this to a client, a committee, or a board—we can help.

Resonanz insights in your inbox...

Get the research behind strategies most professional allocators trust, but almost no-one explains.